Wajeeha Nauman[i], Rida Saeed[ii], Aisha Razzaq[iii], Suman Sheraz[iv]

DOI: 10.36283/pjr.zu.11.2/011

ABSTRACT

Aim: The aim of the study was to determine the frequency of Erb’s palsy, its associated risk factors and health-related quality of life of these patients in Islamabad and different cities of Punjab.

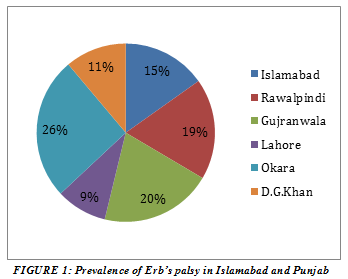

Methodology: A cross-sectional study whereby 242 patients with erb’s palsy were analyzed. Data was collected from different government and private sector hospitals of Islamabad, Rawalpindi, and Lahore, Gujranwala, Okara and D.G khan (Jampur) through direct patient contact and postal and electronic mail during a period of 6 months. Two questionnaires used to assess factors and quality of life, were Questionnaire of Erb’s palsy and WHO Quality of life BREF questionnaire. All patients of erb’s palsy aged below 12 years were included.

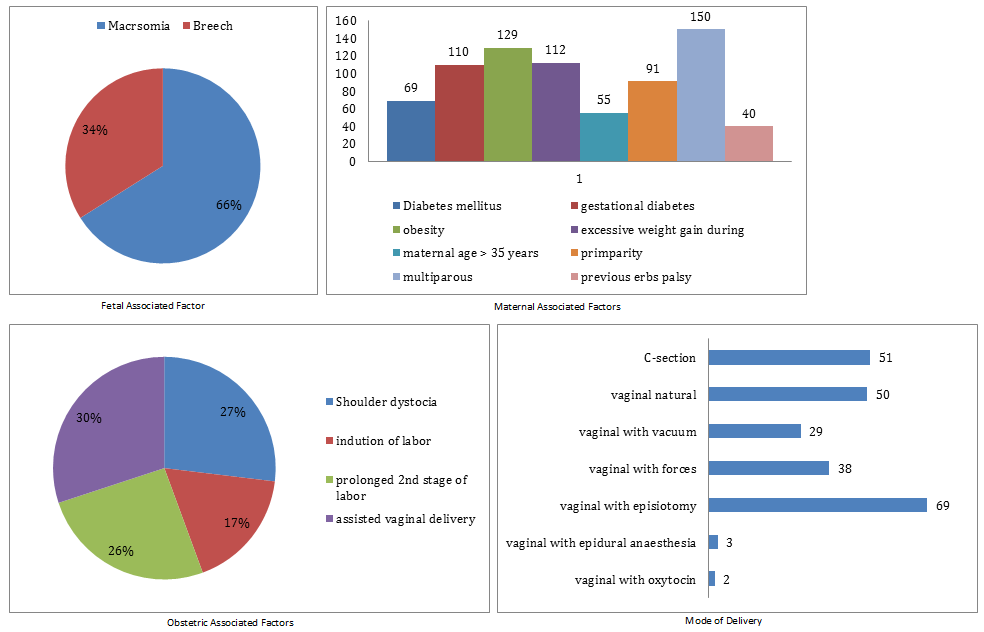

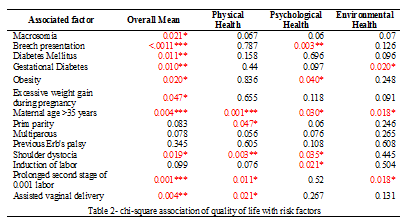

Results: The frequency of Erb’s palsy recorded in Islamabad and different cities of Punjab is about 1.67% with Okara having the highest frequency rate of 3.13%. Among the Fetal-associated factors; Macrosomia 107(44.2%), among Maternal-associated factors; Multiparity 150(62.0%) and among Obstetric-associated factors; assisted vaginal delivery 134(55.4%) had the highest frequency. Quality of life in patients was found to be moderately affected with mean 3.18±0.47 SD. All the physical, psychological and environmental domains were equally affected with mean 3.19±0.39 SD, mean 3.14±0.56 SD and mean 3.22±0.65 SD respectively.

Conclusion: The frequency of Erb’s palsy is highest in Okara among different cities of Punjab and Islamabad, Pakistan. Macrosomia, multiparity and assisted vaginal delivery was the highest associated factors with erb’s palsy. Quality of life was moderately affected in patients with erb’s palsy.

Keywords: Brachial plexus disorders, erb’s palsy, macrosomia, prevalence, Pakistan, quality of life.

Introduction

Erb’s palsy, also known as brachial plexus birth palsy (BPBP), is a flaccid paralysis of the upper extremity diagnosed at time of birth1. Erb’s palsy lesions are common in C5 and C6 nerve roots as they are vertically oriented and at risk of traction injury2. According to the epidemiological studies done to find it’s frequency in different regions, In U.S, incidence rate of erb’s palsy is approximately 1.5 per 1000 live births2, in UK 0.42 per 1000 live births.2 the incidence rate in Pakistan is about 0.07 per 1000 live births in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa3 3.62 per 1000 live births in Karachi, Sindh4 India having prevalence between 0.5 and 4.4 per 1000 live births5.

Erb’s palsy mostly occurs due to excessive downward traction on brachial plexus at anterior shoulder during problematic deliveries. It can also be due to hyperextension of arms during breech vaginal delivery. Other causes can be due to failure of normal rotation of shoulders in oblique position or due to continuous force of posterior shoulder against sacral prominence before delivery6. There are certain risk factors which can lead to Erb’s palsy such as shoulder dystocia, macrosomia, gestational diabetes, persistent fetal head malposition, maternal age and prolonged stage 2 labor7.Other risk factors include breech presentation, multiparity, induction of labor and assisted vaginal delivery8.

Patients with erb’s palsy have a poor quality of life and low self-esteem due to loss of function of upper limbs, which may lead to ultimate disabilities. This highly affects their physical, psychological, emotional, behavioral and socio-economic state of life9. Persistent erb’s palsy can decrease the child’s strength and stamina; impair bone growth, cause muscle atrophy, poor balance and coordination along with abnormal movement and function of joints10.

Several epidemiological studies have been conducted worldwide to find the prevalence, risk factors, and quality of life of patients with Erb’s palsy4, 5,7,8,9 but limited data is available about erb’s palsy prevalence in Pakistan. The rationale of this study is to find the prevalence and associated risk factors of erb’s palsy in Islamabad and Punjab so that these can be taken into account to reduce the occurrence of disease. This study will also highlight the effects on health-related quality of life of Erb’s Palsy children so that these can be worked upon for improvement.

Methodology

The objectives of the study were to find the Prevalence of Erb’s palsy in Islamabad and Punjab. Also, to identify the risk factors and health-related quality of life. The descriptive cross-sectional study on Erb’s palsy was conducted from October’19 to March’20. After taking approval from the institutional ethical review committee, Pediatrics, Gynecological/Obstetrics and Physiotherapy departments were targeted in government hospitals/rehabilitation centers in Islamabad; Pakistan institute of medical sciences (PIMS), National institute rehabilitation medicine (NIRM), Polyclinic hospital, and Capital Hospital (CDA), Rawalpindi; Pakistan railway Hospital (PRH) and Social Security Hospital, Lahore; Children Hospital and Pakistan society of rehabilitation of the disabled (PSRD), Okara; District Headquarter hospital (DHQ), Gujranwala; Rathore medical complex, Jampur (D.G Khan); Tehsil headquarter hospital (THQ) were targeted. Direct, postal, and electronic means were used to get access to the selected population.

The sample size was calculated using the Rao soft calculator with a 5% margin of error, 95% confidence interval (CI), and 50% response rate. As the population size was unknown, it was assumed as 20,000. Total 14,491 patients were approached using purposive non-probability sampling technique, out of which 242 patients who fulfilled the selection criteria i.e. all children aged less than 6 months visiting selected hospitals of Punjab/ Islamabad having Erb’s palsy, were included whereas those who had any associated musculoskeletal and neurological problem other than Erb’s palsy were excluded. Questionnaires of Erb’s palsy and WHO Quality of life were used to assess risk factors and quality of life. Official permission was taken from the WHO to use the questionnaire in the study. After explaining the purpose of the study to the parents of the selected population, questionnaires in English were handed over to them. All subjects and their parents read and signed an institutionally approved informed consent form before the evaluation. Data was analyzed by SPSS version 21. (Statistical Procedure of Social Sciences). Descriptive analysis in terms of percentage and frequency was analyzed. Chi-square association was used to find out the association of the risk factors with the quality of life. Results were described in the form of tables and graphs.

Results

Among 242 patients of Erb’s palsy, the patient’s age was mean ± SD 10.00±7.17 months. The mother’s age at time of delivery was mean ± SD 29.34±6.33 years. The overall frequency of Islamabad and Punjab is estimated to be 1.67% out of a total 14,491 patients.

The frequency of erb’s palsy in Islamabad is calculated to be about 1.84% out of total 5330 patients. Similarly, the frequency calculated for Rawalpindi is 2.22% out of total 1263 patients, in Gujranwala 2.46% out of total 365 patients, in Lahore 1.12% out of total 5700 patients, in Okara 3.13% out of total 1022 patients and in D.G khan (Jampur) 1.35% out of total 811 patients, 167(69.0%) patients were from urban areas and 75(31.0%) were from rural sectors. Basic demographic characteristics of these patients are mentioned in figure 2.

Figure 2- Risk Factors Associated with Erb’s Palsy

Certain fetal associated factors were noticed in these patients among which 107 (44.2%) had macrosomia and 55 (22.7%) had breech presentation. From maternal factors, 69(28.5%) mothers were diabetic, 110(45.5%) had gestational diabetes, 129(53.3%) were obese, 112(46.3%) mothers gained excessive weight during pregnancy, 55(22.7%) mothers over 35 years of age, 91(37.6%) were primparous, 150(62.0%) were multiparous and 40(16.5%) already had previous children with erb’s palsy. From obstetric associated factors, 120(49.6%) had shoulder dystocia, 78(32.2%) had induction of labor, 114(47.1%) had prolonged 2nd stage of labor and 134(55.4%) had assisted vaginal delivery.

From all cases of Erb’s palsy, 108(44.6%) were discovered at time of delivery, 88(36.4) after a week, 36(14.9%) during 1st month, 5(2.1%) during 2nd month and 1st year out of which 154(63.6%) were treated at time of discovery. 41(16.9%) parents opted for treatment from Orthopedics, 19(7.9%) from Neurologist, 88(36.4%) from Physiotherapist, 2(0.8%) from Occupational Therapist and 92(38.0%) from Pediatrics. Out of which only 22(9.1%) underwent surgery. 30(12.4%) cases were totally recovered and 136(56.2%) were partially recovered while 76(31.4%) cases did not recover at all.

Out of patients reported, 187(77.3%) were presented cephalic and 55(22.7%) were presented breech. 193(79.8%) deliveries were made by doctor, 38(15.7%) by midwife and 11(4.5%) by both. 51(21.1%) cases were delivered by C-section, 50(21.1%) by vaginal natural, 29(12.0%) vaginal by vacuum, 38(15.7%) vaginal with forceps, 69(28.5%) vaginal with episiotomy, 3(1.2%) vaginal with epidural anesthesia and 2(0.8%) vaginal with oxytocin. Duration of 2nd stage of labor in hours were asked from all the cases out of which 39(16.1%) had 0.5hrs, 43(17.8%) had 1.00hrs, 7(2.9%) had 1.5hrs, 32(13.2%) had 2hrs, 24(9.9%) had 2.50hrs, 67(27.7%) had 3.00hrs, 15(6.2%) had 3.50hrs, 13(5.4) had 4.00hrs, 1(0.4%) had 4.5hrs and 5hrs. The duration of 2nd stage of labor was mean ± SD 2.11±1.12 hours.

When we analyzed the impact of Erb’s palsy on quality of life of these patients and their parents, we got to know that 2(0.8%) had a very poor and 43(17.8%) had poor quality of life compared with those 102(42.1%) who had no clue about its impact and were very neutral. Only 90(37.2%) were leading a good quality of life and 5(2.1%) were having a very good quality of life. However, the mean ± S.D of all three domains of quality of life were found to be moderately affected by Erb’s palsy.

Erb’s palsy consists of the spectrum of symptoms involving the upper limb mainly. It can be congenital or acquired. This study found the higher Prevalence in Okara is probably because it is an under-developed city with fewer medical facilities and trained staff. Also, because we targeted the major hospital i.e. District Headquarter hospital (DHQ), most of the people from outskirt areas also bring their children here for treatment, hence the increase in reported cases.

The rate of children affected by Erb’s palsy in Karachi, Pakistan was 3.62/1000 live births4. However, the Prevalence of Erb’s palsy in Islamabad and Punjab was 1.67%. When compared to neighboring country India, frequency in Pakistan (1.67%) seems to be higher than the reported rate of India i.e. 0.5-4.4/1000 live births5. One reason for this increase is due to the larger study area targeted in Pakistan compared to India which only included one tertiary care Hospital in their study.

Similarly, frequency in Pakistan (1.67%) seems to be higher than the estimated rates of Erb’s palsy in western Iraq in 2020 (0.05/1000)11 and Kano state in 2020 (0.004/1000)12. These studies did not specifically target the Erb’s palsy patients but rather all patients of birth trauma were included out of which the rate of children with Erb’s palsy was calculated. On the contrary, frequency in Pakistan (1.67%) was identified to be less than that stated in Ghana in 2019 (14.7%) 13.

Macrosomia and breech presentation were reported as major associated fetal factors with Erb’s palsy. This is supported by previous studies that show macrosomia, breech presentation is the highest associated risk factor associated with Erb’s palsy14, 15, and 16. Main reason for this is the fact that babies having higher birth weight undergoes difficult deliveries, mostly with the assistance that damages the brachial plexus if not done properly. This is also supported by a retrospective study done in 2020 stating that higher birth weight increases the chance of developing Erb’s palsy17. These risk factors may predispose Erb’s palsy in different ways18.

Out of all maternal factors, the highest association of Erb’s palsy is with multiparous and obese mothers. Both these factors contribute to gestational diabetes that is also associated with the presence of Erb’s palsy. Rodney et al state that Erb’s palsy is associated with multiparous women having more than 1 baby; a reason for this is that these women experience pregnancy even in their late thirties which further complicates their pregnancy putting the baby at risk for Erb’s palsy17. Maternal obesity and gestational diabetes are the most significant factors that affect the growth of the fetus15, 16. Birth injuries were common in infants of mothers that were obese or multiparous. Studies also showed that an increase in maternal pre-delivery BMI increased the risk of birth injuries19, 20.

Out of four obstetric factors, the study showed that most cases of Erb’s palsy had undergone assisted vaginal delivery with or without shoulder dystocia. However, maximum cases did have shoulder dystocia at the time of delivery for which multiple procedures are used either by midwives or doctors. This study showed that a common procedure used by both doctors and midwives was episiotomy. It was also seen that cesarean delivery did not seem to prevent Erb’s palsy, which is likely due to other maternal or fetal factors that contribute to the development of Erb’s palsy. A retrospective cohort by Kate et al identified no significant difference in the number of Erb’s palsy patients that underwent cesarean or vaginal delivery21.

This study found that on average women with Erb’s palsy infants experience a mean of 2.11± 1.1 hours of the second stage of labor regardless of parity. It is considered an important factor for the development of Erb’s palsy because prolonged 2nd stage labor indicates complications that require assistive procedures to deliver the baby. Prolonged 2nd stage of labor more than 3-4 hours are strongly associated with Erb’s palsy22. Louden E et al. recognized prolonged 2nd stage labor of >61.5 mins to be associated with the development of Erb’s palsy which is less than the mean time calculated by the current survey7. Obstetric factors are thought to be responsible mostly for the result of Erb’s palsy23.

According to the current survey, statistical analysis of the quality of life of patients indicated that Erb’s palsy had a moderate effect on their lives irrespective of the physical, psychological, and environmental health domains. Deficits in abilities to physically function in daily life were noticed but were compensated with secondary strategies including surgical operations to minimize complications. Elassal suggests early surgical intervention should be used to achieve the most benefit24. Psychological health was made better by support from friends and family whereas environmental health issues were sorted by access to healthcare facilities in or near the area of residence. A severe difficulty in movement pattern and function of the upper limb is observed in infants with Erb’s palsy25. The overall quality of health is severely disturbed in infants with Erb’s palsy.

Conclusion

The frequency of Erb’s palsy patients is highest in Okara among major cities of Punjab and Islamabad, Pakistan. Macrosomia, multiparity, and assisted vaginal delivery were the highest associated factors with Erb’s palsy. Quality of life was moderately affected in patients with Erb’s palsy.

References

- Stutz C. Management of Brachial Plexus Birth Injuries: Erbs and Extended Erbs Palsy. InOperative Brachial Plexus Surgery 2021 (pp. 583-590). Springer, Cham.

- Yarfi C, Elekusi C, Banson AN, Angmorterh SK, Kortei NK, Ofori EK. Prevalence and predisposing factors of brachial plexus birth palsy in a regional hospital in Ghana: a five year retrospective study. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2019;32.

- Mohammad A, Khattak AK, Hayat M, Mohammad L. patteren of birth trauma in newborn presenting to neonatology unit of a tertiary care hospital at peshawar. KJMS. 2017;10(3):331.

- Shabbir S, Zahid M. Risk Factors and incidence of Birth Trauma in Tertiary Care Hospital of Karachi. Pak J Surg. 2015;31(1):66-9.

- Hasabe RA, Diwane DS, Chandawar SS. A two-year retrospective study of infants with Erb-Duchenne’s palsy at a tertiary centre in Rajasthan, India. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018 Feb 1;7(2):700-4.

- Al-Hiali SJ, Muhammed A, Khazraji AA. Prevalence, Types, and Risk Factors of Birth Trauma Among Neonates atAl-Ramadi Maternity and Children Teaching Hospital, Western Iraq. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2020 Nov;23:231-812.

- Louden E, Marcotte M, Mehlman C, Lippert W, Huang B, Paulson A. Risk factors for brachial plexus birth injury. Children. 2018;5(4):46.

- Belabbassi H, Imouloudene A, Kaced H. Risk factors for obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Mustansiriya Medical Journal. 2020 Jan 1;19(1):30.

- Estrella EP, Castillo-Carandang NT, Cordero CP, Juban NR. Quality of life of patients with traumatic brachial plexus injuries. Injury. 2021 Apr 1;52(4):855-61.

- Basit H, Ali CDM, Madhani NB. Erb Palsy. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing; 2019.

- Al-Hiali SJ, Muhammed A, Khazraji AA. Prevalence, Types, and Risk Factors of Birth Trauma Among Neonates atAl-Ramadi Maternity and Children Teaching Hospital, Western Iraq. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2020;23:231-812.

- Badaru U, Ma’aruf I, Ahmad R, Lawal I, Usman J. Prevalence and pattern of paediatric neurological disorders managed in outpatient physiotherapy clinics in Kano. Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences. 2020;12(2):201-6.

- Cosmos Y, Cephas E, Nkrumah BA, Kwadjo AS, Korley KN, Ofori EK. Prevalence and predisposing factors of brachial plexus birth palsy in a regional hospital in Ghana: a five year retrospective study. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2019;32.

- Vakhshori V, Bouz GJ, Alluri RK, Stevanovic M, Ghiassi A, Lightdale N. Risk factors associated with neonatal brachial plexus palsy in the United States. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 2020 Jul 1;29(4):392-8.

- Belabbassi H, Imouloudene A, Kaced H. Risk factors for obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Mustansiriya Medical Journal. 2020 Jan 1;19(1):30.

- Van der Looven R, Le Roy L, Tanghe E, Samijn B, Roets E, Pauwels N, Deschepper E, De Muynck M, Vingerhoets G, Van den Broeck C. Risk factors for neonatal brachial plexus palsy: a systematic review and meta‐ Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2020 Jun;62(6):673-83.

- Jeevannavar JS, Appannavar S, Kulkarni S. Obstetric Brachial Plexus Palsy-A Retrospective Data Analysis. Indian Journal of Physiotherapy & Occupational Therapy. 2020;14(1).

- Vakhshori V, Bouz GJ, Alluri RK, Stevanovic M, Ghiassi A, Lightdale N. Risk factors associated with neonatal brachial plexus palsy in the United States. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 2020 Jul 1;29(4):392-8.

- McLaren Jr RA, Chang KW-C, Ankumah N-AE, Yang LJ-S, Chauhan SP. Persistence of Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy among Nulliparous Versus Parous Women. American Journal of Perinatology Reports. 2019;9(01):e1-e5.

- Avram CM, Garg B, Skeith AE, Caughey AB. Maternal body-mass-index and neonatal brachial plexus palsy in a California cohort. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021 Jun 5:1-8.

- Dow ML, Szymanski LM. Effects of overweight and obesity in pregnancy on health of the offspring. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics. 2020 Jun 1;49(2):251-63.

- Vakhshori V, Bouz GJ, Alluri RK, Stevanovic M, Ghiassi A, Lightdale N. Risk factors associated with neonatal brachial plexus palsy in the United States. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 2020 Jul 1;29(4):392-8.

- Infante-Torres N, Molina-Alarcón M, Arias-Arias A, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A. Relationship Between Prolonged Second Stage of Labor and Short-Term Neonatal Morbidity: A Systematic Review and

- Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(21):7762.

- Galbiatti JA, Cardoso FL, Galbiatti MG. Obstetric Paralysis: Who is to blame? A systematic literature review. Revista brasileira de ortopedia. 2020 May 15;55:139-46.

- Medeiros DL, Agostinho NB, Mochizuki L, Oliveira AS. Quality of life and upper limb function of children with neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Revista Paulista de Pediatria. 2020 Mar 9;38.

The Ziauddin University is on the list of I4OA (https://i4oa.org/) & I4OC (https://i4oc.org/).

![]() This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Conflict of Interest: The author (s) have no conflict.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Conflict of Interest: The author (s) have no conflict.

[i] Student Riphah international university.

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-6911-3976

[ii] Assistant professor, Faculty of Rehabilitation and Allied health sciences, Riphah international university.

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-5764-3638

[iii] Student Riphah international university.

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0270-4493

[iv] Assistant professor, Faculty of Rehabilitation and Allied health sciences, Riphah international university.

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-1441-1455