Mehwish Iqbal[i]

DOI: 10.36283/pjr.zu.11.2/021

ABSTRACT

Background and Aims: Children with autism and sensory processing disorder may suffer from issues in interoception or its awareness. However, limited studies have been conducted till date this study is aimed to assess the interoceptive awareness among children with autism and sensory processing disorder.

Methodology: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on autistic children to observe interoception through a self-administered questionnaire based on emotional awareness, self-regulation and body awareness formulated on Google Docs and distributed via email or Whatsapp group.

Results: A total number of 63 children consisted of 42 (67%) males and 21 (33%) females showed that (30.3%) children were always able to recognize their anger, (47.6%) feels pain in their body, (58.7%),feel and inform their parents while only (19%) children knows and feel about their mouth being dry or about their thirst. During eating, the (76.2%) children never have difficulty coordinating swallowing, chewing or sucking with breathing. In toileting routines, (41%) and (28.6%) always communicated regarding urination and defecation.

Conclusion: It was concluded that less notable interoceptive differences were found in the children with autism; however, future trials may use standardized approaches to rule out such components in autistic children for effective care and management of the disability.

Keywords: Sensations, awareness, emotions, hunger, thirst, disability.

Introduction

Autism is a developmental disease in which a person’s capacity to communicate, make interpersonal relationships, and interaction with the environment is impaired. A number of studies have found that people with autism have trouble planning and executing emotions27. It’s a condition characterized by a, primary symptoms, lack of social contact28. Besides, a neurological condition, known as Sensory Processing Disorder in children, in which the brain does not interpret the received information in an ordered way which eventually results in poor emotional regulation4. For children who have high functioning autism, the occurrence of sensory problems is observed5,6. Conditions like Autism Spectrum Disorder, Trauma, Depression, and Obesity, etc. are found to show interoception deficiencies that may potentially impair adults’ physical and mental health, social relationships, and self-awareness2. When impaired cognitive pathways make it difficult to avoid the epiphenomenal connection between body physiology and emotions, interoceptive impulses are used8. Furthermore, some existing sensory systems also tend to be disrupted in autism9,10. Despite the fact that Autism Spectrum is primarily classified as a social and cognitive disorder, strong evidence suggests that it also includes severe sensory-motor issues (ASD). The Movement Evaluation Battery for Children (M-ABC2) was used to conduct an initial wide examination, which was followed by a specific kinematic assessment. ASD impairment in the broad categories of manual dexterity and ball skills, in particular, was found to be linked to specific difficulties on isolated tasks, which were converted into targeted experimental assessments. The use of perception-action coupling to lead, modify, and customize movement to task demands is impaired in both following investigations, resulting in inflexible and rigid motor profiles. The utilization of temporal adaptability is particularly difficult, as seen by “hyper dexterity” in ballistic movement profiles, typically at the expense of spatial accuracy and task performance. Clear and defined linkages are drawn between measurable issues and underlying sensory-motor evaluation by proceeding linearly from the use of a standardized assessment tool to focused kinematic examination. The findings are interpreted in light of perception-action coupling and its function in early infant development, implying that sensory-motor impairment is a “secondary” level impairment rather than a “secondary” level impairment26.

Despite the fact that motor milestones are not generally connected with autistic behavior, there is accumulating evidence that a significant proportion of people with autism are delayed in reaching them and/or have abnormal motor control. Only a few researches have gone beyond broad assessments of general delays and timing variations to investigate what exactly is distinctive about autism-related motions31. The 8th Sense can determine the internal body sensations for the heavy eyelids, tensing of muscles, movements of stomach muscles during digestion, and convey the emotions1,2. This perception is called “Interoceptive Awareness” that tends to play a vital role by structuring perceptions of being and possessing a body3. However, interoceptive processing in autistic people may have a different lifespan as compared to normally developing individuals11 because of the atypical integration of internal afferents and multiple sensory connections3,12. These signals have less impact on ASD decision making and stress the role of difficulties in identifying, processing, or describing emotions13. Besides, the poor developed interoception’s consequences may cause difficulties with social skills and emotions, thus requiring their facilitators to have higher levels of co-regulation1. However, effective interception conditions are frequently unclear and are challenging to monitor when identified14. A study conducted to investigate the interoception and body awareness in adults with and without autism reported that the ASD group had low thirst and body awareness in comparison with the non-ASD group2. Similarly, another study performed a paradigm of heartbeat perception as a measure of interoceptive ability demonstrated that ASD children were better or their heartbeats psychologically over longer periods. Thus, indicated improved sustained sensitivity to internal signals. However, awareness was found to be negatively associated9. Another review showed that due to sensory processing issues in the interoceptive area among ASD children showed a minor inclination towards interoceptive hypoactivity12.

Another study showed a clinically important lower perception of body and thirst relative to the control group2,7. A trial conducted by Shah, Catmur and Bird13 in 2016 stated remarkable deviation between the autistic and people without neurological issues suggested that interoception has less influence on the role of alexithymia5. Several studies showed the effectiveness of the intervention on increasing the sense of interoception catering to occupational performance and emotional regulation therefore authors promote further investigations on a large number of population7.

Studies demonstrated that the effect of interoception goes beyond homeostasis; enthusiasm and emotion i.e. the affective thoughts and behaviors of oneself and self-awareness that are suggested to be central8. In spite, these children show less awareness toward pain responses which could be a big issue. Moreover, there is a mutual connection between vision and signals from the body which creates body consciousness15. A study also observed that in autism, visual perception and eye tracking deficits have been identified16. Therefore, a number of trials should be conducted to determine the consequences of interoceptive deficits in autistic and children with sensory processing disorders.

A limited yet increasing levelof understanding related science work on interoception in ASD is present12. The curiosity of researchers in ASD detection is growing on how the quality of life is measured by interoception, recognition and comprehension17. While interoceptive training is a promising possibility yet it remains to be seen whether or not it contributes to transferable improvements in social-emotional processing as indicated7. Therefore, this study will be conducted to assess the interoception in children with autism and sensory processing disorder using self-administered questionnaires. In addition to having difficulty in executing more complex movements, participants with ASD also experience more irregularity when executing relatively easy movements. In the accuracy of primary and catch up saccades participants with ASD show increased variability while whole oculomotor control seems to be maintained 29.

Methodology

Study Setting

This study was conducted in rehabilitation centers of Karachi including Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (IPM&R), Liaquat National School of Physiotherapy (LNSOP) and Dr. Ziauddin Hospital, North and Clifton campuses.

Target Population

Children with autism and sensory processing disorders.

Study Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Duration of Study

6-8 months.

Sampling Technique

Non-Probability Convenience Sampling Technique.

Sample Size

n=150

Sample Selection

Inclusion Criteria: Children with autism and sensory processing disorders aged 8-12 years age, diagnosed on DSM IV and V criteria were included.

Exclusion Criteria: Children with other developmental disabilities or refusal to participate in the study were excluded.

Data Collection Tool

Interoception was observed through a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 26 questions based on emotional awareness, self-regulation and body awareness on a scale of “Never” to “Always”.

Data Collection Procedure

Participants were enrolled in study through convenience sampling techniques from different rehabilitation institutes. The questionnaire was formulated in Google Docs and sent to participants via email or Whatsapp group. Prior to collection, all participants were given consent form to ensure their voluntary participation. After their consent, understanding about the questionnaire was ensured in order to record the responses on the interoceptive awareness questionnaire. The data was analyzed upon completion of the sample.

Data Analysis Strategy

Data was analyzed on Google Docs Editor. The demographic characteristics of the participants were represented through frequency, mean and standard deviations whereas the participant responses were evaluated through frequency and percentage.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical consideration was taken via verbal and written Consent by the participant before starting the data collection. All information of the participants was kept anonymous under investigator’s supervision.

Results

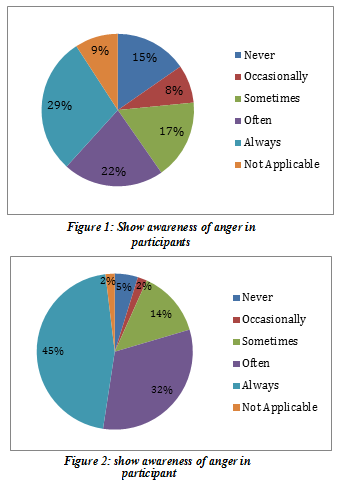

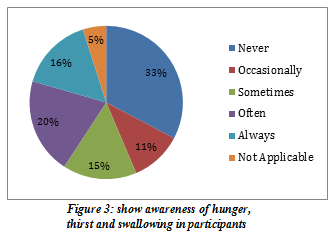

A total number of 63 children enrolled in the study consisted of 42 (67%) males and 21 (33%) females respectively among which majority (52.4 %) were among 3+ years to 6 years of age. The majority of children have Autism Spectrum Disorder (52.4%), Sensory Processing Disorder (23.8%) or (23.8%). In the domain of emotional responses, (30.3%) children were able to always recognize their anger while only (22.2%) recognized it often as shown in Figure-1. Moreover, (47.6%) always feel pain in their body as illustrated in Figure-2. However, (33%) of the kids sometimes ignore the pain felt in their body.

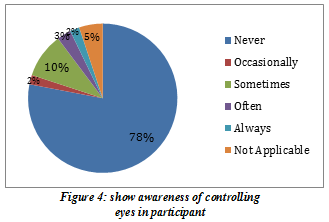

Interoceptive awareness results regarding hunger, thirst, chewing swallowing shows remarkably prominent patterns, (58.7%).

Children always feels and tell their parents that they are hungry while only (19%) children know and feel about their mouth being dry or about their thirst. While eating, the (76.2%) children never have difficulty coordinating swallowing, chewing or sucking with breathing, (66.7%) never gag while eating, (61.9%) of the kids never had the continuous urge to swallow the saliva in their mouth as shown in Figure-3.

In toileting routines, (41%) always tell and feel the need of urination while however (22.2%) never tell the need of urination as shown in Figure-5. On the other hand, (28.6%) always knows and tells about the need for defecation, (14.3%) often tells about it, however (22.2%) of the children never feel about the urge as presented in Figure-6. Moreover, (61.9%) parents were concerned that their kids never tell whenever they had constipation. Furthermore, (33.3%) children never had difficulty controlling their eyes while (20.6%) faced difficulty sometimes and (15.9%) of the kids always had issues as shown in Figure-4.

Furthermore, the results explained the distressing situation that around half of the children were never able to feel the temperature of their face, more than half of them didn’t feel that they were sweating in palms and armpits and around 60% of the population never felt the goose bump.

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that (30.3%) children were able to always recognize their anger, (47.6%) always feels pain in their body, (58.7%) children always feels and tell their parents that they are hungry while only (19%) children knows and feel about their mouth being dry or about their thirst. While eating, the (76.2%) children never have difficulty coordinating swallowing, chewing or sucking with breathing. In toileting routines, (41%) and (28.6%) always tell and feel the need of urination and defecation. Furthermore, the results explained the distressing situation that around half of the children were never able to feel the temperature of their face, more than half of them didn’t feel that they were sweating in palms and armpits and around 60% of the population never felt the goose bumps.

Differences in the latency and execution of eye are lacking over all, individuals with ASD having consistent difficulty in movement when integration between brain areas is required. The major goals of the present study were to learn more about how people with autism conduct rapid manual targeting motions and to figure out why there are so many disparities in movement performance. A study conducted in-depth assessments of acceleration, velocity, and deceleration.

Both spatial and temporal diversity, all of which contribute to a better understanding of how people with autism plan and execute small rapid targeting actions. Because of the limited number of participants and wide range of verbal and nonverbal abilities, the results of this study should be regarded as preliminary.30 The new findings, on the other hand, are in line with prior research and extend those findings to young people with autism. For example, participants with autism required longer time to initiate and execute their motions, which was consistent with prior research. Despite the short sample size, there was a substantial link between verbal ability and reaction time, verbal ability and movement time, and nonverbal ability and reaction time. Participants with better verbal abilities initiated and completed their activities more quickly than those with lower verbal abilities in the current study. Participants with better nonverbal ability also started their movements faster, although the association between movement time and nonverbal ability was not as strong. Again, the number of participants was insufficient to do a correlation analysis. The current findings, however, are comparable to those, in that there was a link between linguistic ability and level of functioning and motor performance. More quickly, there is still a significant and continuous difference between people with autism and those without autism32.

The results of the study demonstrated that interoceptive issues are more common in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder due to the regulation of the hormone known as oxytocin that is typically affected in their childhood. This may lead to severely create defects in the sensory-motor, autonomic, behavioral, and cognitive areas18. Latter explained alexithymia, not autism, results in poor functioning of interoception17. However, another study explained that adult people with autism showed no evidence of interoceptive dysfunction19. Moreover, a study states that stress and adverse life experiences adversely affect the willingness of an individual that may affect the ability to detect interoceptive signals20. Besides, our study evaluates the components which are the major causes that lead to interoception dysfunction and considered as a somatic symptom disorder. Moreover, emotion, urges, feelings, drives, and adaptive responses are assumed as a major component of interoceptive signals8. Another study was conducted to understand interoceptive factors included pain, proprioceptive issues, emotions, and issues related to Gastrointestinal systems21demonstrated that more than half of the children always feel the hunger pangs but few of them were able to figure out the need of water when feeling thirsty, similarly another study demonstrated that those who had ASD showed a clinically relevant lower thirst awareness2. Furthermore, interoception is substantial for a person’s well-being9. As defecation and urination are major health factors, thus may get affected if not regulated at the earliest stage22. Moreover, our study observed that the parents of the targeted population were concerned about the toileting instincts including urination and defecation of their children23. Moreover, parents sharing worries about toileting may lead to substantial discomfort24. Besides, it is known that people with autism spectrum disorder may have a poor ability to incorporate interoceptive information which may lead to a limited emotional and behavioral drive25. Despite the fact, due to the small sample size more accurate results can be emerged to reveal that which component needs the most urgent attention of the caregiver and therapist.

Strength

To the best of author’s knowledge, this study is the first to be conducted in Pakistan highlighting the concept of interoception and its role in children with disabilities. Furthermore, the study also evaluated multiple sensory experiences that may serve as the basis for future trials.

Limitations

Several limitations occurred in this study including the appropriate diagnosis of the interoceptive awareness. Despite this, small sample size also causedlimitation to generalize the results. Moreover, gender wise disparities were not evaluated.Future Directions

A number of trials are recommended for the future to evaluate the factors associated with interoception and to rule out possible management related to it.

Conclusion

It was concluded that IPSB is indeed present in healthcare workers; however the percentage is comparatively low. However, few have expressed their disgust and raised voices to report the issues. Therefore, future studies should be conducted considering therapists training and awareness to identify such red flagsin their settings and inform the management to take required steps to address it.

References

- Goodall E. Interoception as a proactive tool to decrease challenging behaviour. Scan: The Journal for Educators. 2020;39(1):20.

- Fiene L, Brownlow C. Investigating interoception and body awareness in adults with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research. 2015 Dec;8(6):709-16.

- Seth AK, Frion KJ. Active interoceptive inference and the emotional brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2016 Nov 19;371(1708):20160007.

- Khan I, Khan MA. Sensory and Perceptual Alterations. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Oct 12.

- Mul CL, Stagg SD, Herbelin B, Aspell JE. The feeling of me feeling for you: Interoception, alexithymia and empathy in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018 Sep 1;48(9):2953-67.

- Minshew NJ, Hobson JA. Sensory sensitivities and performance on sensory perceptual tasks in high-functioning individuals with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2008 Sep 1;38(8):1485-98.

- Hample K, Mahler K, Amspacher A. An Interoception-Based Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2020 Mar 22:1-4.

- Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN. The influence of physiological signals on cognition. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2018 Feb 1;19:13-8.

- Farb N, Daubenmier J, Price CJ, Gard T, Kerr C, Dunn BD, Klein AC, Paulus MP, Mehling WE. Interoception, contemplative practice, and health. Frontiers in psychology. 2015 Jun 9;6:763.

- Marco EJ, Hinkley LB, Hill SS, Nagarajan SS. Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatric research. 2011 May;69(8):48-54.

- Fotopoulou A, Tsakiris M. Mentalizing homeostasis: The social origins of interoceptive inference. Neuropsychoanalysis. 2017 Jan 2;19(1):3-28.

- DuBois D, Ameis SH, Lai MC, Casanova MF, Desarkar P. Interoception in autism spectrum disorder: A review. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2016 Aug 1;52:104-11.

- Shah P, Catmur C, Bird G. Emotional decision-making in autism spectrum disorder: the roles of interoception and alexithymia. Molecular autism. 2016 Dec 1;7(1):43.

- Brener J, Ring C. Towards a psychophysics of interoceptive processes: the measurement of heartbeat detection. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2016 Nov 19;371(1708):20160015.

- Faivre N, Salomon R, Blanke O. Visual consciousness and bodily self-consciousness. Current opinion in neurology. 2015 Feb 1;28(1):23-8.

- Takarae Y, Luna B, Minshew NJ, Sweeney JA. Patterns of visual sensory and sensorimotor abnormalities in autism vary in relation to history of early language delay. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008 Nov;14(6):980-9.

- Brewer R, Happé F, Cook R, Bird G. Commentary on “Autism, oxytocin and interoception”: Alexithymia, not Autism Spectrum Disorders, is the consequence of interoceptive failure. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015 Sep 1;56:348-53.

- Quattrocki E, Friston K. Autism, oxytocin and interoception. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2014 Nov 1;47:410-30.

- Nicholson TM, Williams DM, Grainger C, Christensen JF, Calvo-Merino B, Gaigg SB. Interoceptive impairments do not lie at the heart of autism or alexithymia. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2018 Aug;127(6):612.

- Price CJ, Hooven C. Interoceptive awareness skills for emotion regulation: Theory and approach of mindful awareness in body-oriented therapy (MABT). Frontiers in psychology. 2018 May 28;9:798.

- Cameron OG. Interoception: the inside story—a model for psychosomatic processes. Psychosomatic medicine. 2001 Sep 1;63(5):697-710.

- Little LM, Benton K, Manuel-Rubio M, Saps M, Fishbein M. Contribution of Sensory Processing to Chronic Constipation in Preschool Children. The Journal of pediatrics. 2019 Jul 1;210:141-5.

- McLay L, Blampied N. Toilet training: Strategies involving modeling and modifications of the physical environmental. InClinical guide to toilet training children 2017 (pp. 143-167). Springer, Cham.

- Macias MM, Roberts KM, Saylor CF, Fussell JJ. Toileting concerns, parenting stress, and behavior problems in children with special health care needs. Clinical Pediatrics. 2006 Jun;45(5):415-22.

- Hatfield TR, Brown RF, Giummarra MJ, Lenggenhager B. Autism spectrum disorder and interoception: Abnormalities in global integration?. Autism. 2019 Jan;23(1):212-22.

- Whyatt C, Craig C. Sensory-motor problems in Autism. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2013 Jul 18;7:51.

- Nazarali N, Glazebrook CM, Elliott D. Movement planning and reprogramming in individuals with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2009 Oct 1;39(10):1401-11.

- Glazebrook CM, Elliott D, Szatmari P. How do individuals with autism plan their movements?. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2008 Jan 1;38(1):114-26.

- Nowinski CV, Minshew NJ, Luna B, Takarae Y, Sweeney JA. Oculomotor studies of cerebellar function in autism. Psychiatry research. 2005 Nov 15;137(1-2):11-9.

- Courchesne E, Pierce K. Brain overgrowth in autism during a critical time in development: implications for frontal pyramidal neuron and interneuron development and connectivity. International journal of developmental neuroscience. 2005 Apr 1;23(2-3):153-70.

- Glazebrook CM, Elliott D, Lyons J. A kinematic analysis of how young adults with and without autism plan and control goal-directed movements. Motor control. 2006 Jul 1;10(3):244-64.

- Mari M, Castiello U, Marks D, Marraffa C, Prior M. The reach–to–grasp movement in children with autism spectrum disorder. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003 Feb 28;358(1430):393-403.

The Ziauddin University is on the list of I4OA (https://i4oa.org/) & I4OC (https://i4oc.org/).

![]() This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Conflict of Interest: The author (s) have no conflict.

[i] Lecturer/Occupational Therapist Sindh Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5738-8371