Rizwana Waheed[i]

DOI: 10.36283/pjr.zu.11.2/022

ABSTRACT

Background and Aims: Number of studies in healthcare context has described the rehabilitators as harassment perpetrator and patient as the victim, in particular therapists. Therefore, these issues must examine the dynamics of patient-therapists’ relationships to understand the factors related to the inappropriate sexual behavior.

Methodology: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on physical and occupational therapists, recruited via convenience sampling technique. The data was collected through Inappropriate Patient Sexual Behavior questionnaire, sent to participants via email or WhatsApp groups.

Results: A total number of 106 participants including 12.3% males and 87.7% females with 71.7% physical and 28.3% occupational therapist. The finding revealed that 82.1% therapists never had training in the context of understanding the inappropriate patient sexual behavior. Whereas 28.3% revealed that a patient has stared the body that made them uncomfortable, 9.5% reported to have sexual flattering remarks, 4.7% had purposeful touched in a sexual manner. Unfortunately, only 37.7%has expressed their disgust and raised voice to report the issues.

Conclusion: It was concluded that relatively very low percentage of IPSB is present and reported cases are usually recorded as disgust feeling or raised voice. Thus for healthy therapeutic relationship, training for handling obscene behavior must be conducted and the curriculum should promote knowledge of this aspect.

Keywords: Sexual harassment, gender, work place, victim, assault, obscene behavior.

Introduction

Harassment is outlined as any dishonourable or unwelcome conduct that may be anticipated to offend another individual, may occur concerning certain words, signals, or activities that tend to bother, alert, manhandle or humiliate another, besides, it is after scaring, threatening, or hostile work environment1. Sexual harassment is characterized by any unwelcome sexual step, support, verbal-physical conduct, or signal of a sexual nature that might sensibly be seen to cause offense or mortification to another individual2. Such conduct leads to meddling with work or makes a scaring, or antagonistic work environment. Sexual badgering may occur between people of the opposite or same-sex i.e. both males and females can be either the casualties or fugitives3.

Several studies demonstrated that sexual harassment that happens at a moderately tall-rate in a healthcare setting is seemly understandable sexual behaviour towards medical caretakers4,5. Many researchers have reported that health professionals are not always comfortable when dealing with sexual issues that arise in a client’s care. In particular, health professionals may feel uncomfortable to deal with these interactions6. It is generally assumed that to manage these circumstances appropriately, health professionals need to be comfortable with their sexuality. In addition to it, the latter must have the inevitable skills and confidence to deal with these interactions of sexual implications6.

A sort of harassment may also include the utilization of express or understood sexual suggestions, counting the unwelcome, unseemly guarantee of remunerations in trade for sexual courtesies7. According to Gruber and Fineran8, sexual harassment was initially defined as behaviour by those individuals who utilized organizational control for their social benefit to restrain sexual favours from females. Besides, it is accepted by many social scientists that status and control are important for understanding the origins of sexual badgering. Some authors have recommended that health care labourers are regularly not arranged for the plausibility of harassment by patients and respond in means that supplements the probability of such behaviour reoccurring9. Furthermore, several pieces of research have documented sexual harassment from patients; however, the literature is confined in its scope. Health professionals who are suffering from sexual situations may at the risk of neglecting specific healthcare concerns in their patients that will negatively impact the services. This may lead to a barrier to appropriate therapeutic intervention, however, health professionals will be able to deliver appropriate services if they are affirmed to deal with a range of sexual interactions10. A survey was conducted on understudies’ physical specialists and therapists revealed that the larger part of respondents 80.9% have experienced a few levels of IPSB even though nearly half of the one-third of the third and fourth-year understudies has encountered serious IPSB that counts for forceful sexual touching and ponder sexual introduction11. Moreover, 20% of the respondents perceived sexual harassment. Therefore, it is concluded that this issue is ought to be addressed by consideration of instruction programs for understudies and physical advisors at the level of consolation amid clinical intelligent that have sexual suggestions12.

Another study reported that more than half of the understudies expected that they would not feel comfortable in managing sexual issues, as being most awkward with were masturbation, unmistakable, and incognito sexual remarks13. It was also reported that understudies felt moderately comfortable with homosexual males. Despite this, a survey showed that a handicapped person was sought for sexual options14. Moreover, at the slightest half, the senior understudies accepted that their instructive program had not managed enough with sexual issues thus, assisted inquiry about exploring the nature and beginning of nuisance is prescribed in managing with sexual issues15. Sexual badgering happens to be challenging the wellbeing and security of medical caregivers affecting the quality and proficiency. Predominantly, female workers confront sexual badgering in working environment settings16. It was reported that the caregivers portrayed an assortment of seen shapes of sexual badgering within the clinical setting. They also explained patient-perpetrated occurrences as the foremost debilitating to recognize in comparison to specialists and co-workers17. There was noteworthy equivocalness concerning sexual impelling in connections to female caregivers in particular. This was depicted as holding potential for misuse or sexual badgering18. Besides, the female caregivers detailed that normal responses to sexual badgering were inactive or casualty accusing was endeavored to formally reported episodes. They demonstrated that environmental sexual badgering has contributed to negative societal demeanors. Therefore, procedures such as teamwork, monitoring, and social support should be acquired to secure themselves from sexual badgering. Moreover, viable neighborhood avoidance and mediation reactions should be investigated required to decide the greatness of the issue in contrast to sexual badgering based on culprit expectation, and individual vulnerabilities19. Amid healthcare practice, physical and occupational therapists may experience this sort of behaviour frequently involving working staff, colleagues, and patients. However, no information exists concerning how far-reaching the Inappropriate Patient Sexual Behaviour (IPSB) is in physical and occupational therapy practices. Despite, therapists may be included in examining clients’ sexual concerns and performing appraisals that might include insinuating touch therefore the nature of such evaluations can put therapists in a position where they ought to bargain with unseemly sexual conduct in their client20. Further, both occupational and physical therapy treatment included touching the persistent and near associate-individual connections. Thus, it is clear that the issue of IPSB within the occupational and physical treatment practices is not well-documented.

Study setting

Data was collected from rehab department of primary and tertiary care hospitals.

Target Population

Occupational and Physical Therapists.

Study Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Duration of Study

6-8 months.

Sampling Technique

Non-Probability Convenience Sampling Technique.

Sample Size

n=106

Sample Selection

Inclusion criteria: Male and female occupational and physical therapists working in primary or tertiary care hospital for > 2 years.

Exclusion criteria: Refusal of participation or not working currently in clinical settings.

Data Collection Tool

Inappropriate Patient Sexual Behavior (IPSB) questionnaire comprised of total 25 questions based on three sections including demographics, patient care and behavior, inappropriate patient sexual behavior and reporting issue and coping strategy on varying options.

Data Collection Procedure

Participants were enrolled in study through convenience sampling technique from primary and tertiary care hospitals. The questionnaire was formulated in Google Docs and sent to participants via email or WhatsApp group. Prior to collection, all participants were given consent form to ensure their voluntary participation. After their consent, understanding about the questionnaire was ensured in order to record the responses on the IPSB questionnaire. The data was analyzed upon completion of sample.

Data Analysis Strategy

Data was analyzed on Google Docs Editor. The demographic characteristics of the participants were represented through frequency, mean and standard deviations whereas the participant responses were evaluated through frequency and percentage.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical consideration was taken via verbal and written consent by the participant before starting the data collection. All information of the participants will be kept anonymous under investigator’s supervision.

Results

A total number of 106 participants out of which 12.3% are males and 87.7% females including 71.7% physical and 28.3% occupational therapists respectively included with highest number of responses reported under <30 years’ age. The demographic details are depicted in Table-1.

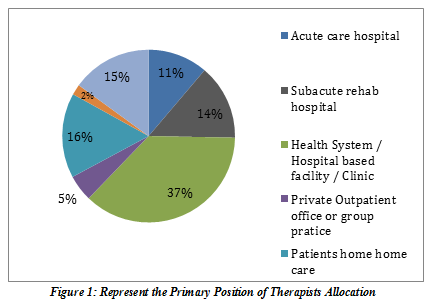

It was revealed that 69.8%therapists have provided the direct patient care for 0-5 years, followed by 17% for 11-20 years and 9.4% for 6-10 years working in hospital-based outpatient facility/clinic 37.7%, patient home care 16%, academic institution 15.1%, in-patient wards 14.2% and acute care hospital 1.3% as a full-time 60.4% and part-time 30.2% therapists respectively. The description is illustrated in Figure-1.

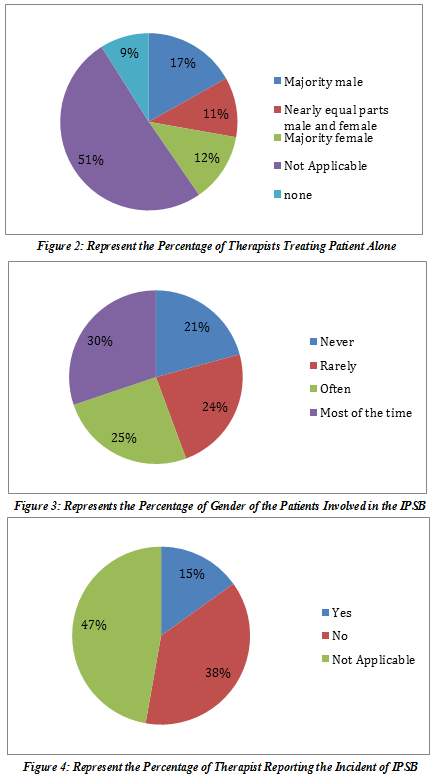

It has been reported that 90.6% therapists have treated patients in the last year involving mostly women 53.8%, both men and women 30.2% and men 8.5% in private rooms/booth 25.5% and most of the time alone 30.2% as shown in Figure-2.

It was revealed that 82.1% therapists never had training in the context of understanding the inappropriate patient sexual behavior. Moreover, 28.3% answered that a patient has stared the body that made them uncomfortable, 9.5% reported to have sexual flattering remarks, 6.6% faced sexually suggestive gestures, 2.8% has asked for a date whereas none of the therapists has received any sexual/romantic gift. Moreover, 4.7% had purposeful touched in a sexual manner while 1.9% was harassed outside the workplace? However, among these cases, only 10.4% men and women were perpetrators, while 17% women 16% men were involved as shown in Figure-3.

Due to these incidents, 27.4% therapists distracted or redirected the patient with alternate activity whereas 23.6% have ignored or pretend it never happened, moreover 30.2% considered to treat the patient more in public space or select a different treatment method with less physical contact. Unfortunately, only 37.7% has expressed their disgust and raised voice to report the issues as shown in Figure-4.

Discussion

The finding of this study revealed that 82.1% therapists never had training in the context of understanding the inappropriate patient sexual behavior. Moreover, 28.3% answered that a patient has stared the body that made them uncomfortable, 9.5% reported to have sexual flattering remarks, 6.6% faced sexually suggestive gestures, 2.8% has asked for a date whereas none of the therapists has received any sexual/romantic gift. Moreover, 4.7% had purposeful touched in a sexual manner while 1.9% were harassed outside the workplace. However, among these cases, only 10.4% men and women were perpetrators, while 17% women 16% men were involved. Unfortunately, only 37.7% has expressed their disgust and raised voice to report the issues. This showed that IPSB is indeed present in healthcare workers, however comparatively less as compared to Western countries. This IPSB survey was conducted to the primary endeavour to distinguish the occurrence of the issue among the therapists. A brief report indicated that few respondents have accepted neurology to be a key for the event of IPSB (Ilik et al., 2020). Although, the factors related to it are not yet clear. However, the findings of the study revealed that the percentages of both physical and occupational therapists reporting sexual harassment are not significantly high. The answers of respondents towards question regarding the IPSB although portrayed behaviours of sexual badgering. However, it is evident, that the respondents don’t see IPSB as sexual badgering. Yet few respondents reported having been sexually annoyed, which may not be an astounding but alarming situation.

A study conducted by Fitzgerald and Cortina (2018) proposed an attribution show to clarify people’s beneath-standing of sexual badgering that individuals decipher behaviours in terms of perceived causes may not have credited the behaviours to sexual badgering. Moreover, quiet behaviour may not have been seen as threatening or insensible. Besides, unwillingness to name IPSB as sexual badgering may have become a great circumstance to a great extent that has been overlooked in healthcare foundation (Khanna, 2019). Notwithstanding, whether IPSB is labelled as sexual badgering, such behaviours lead to several returns and consequently are an issue for the therapists (Hadjicharalambous and Sisco, 2016).

Studies demonstrated that sexual harassment affects proportionately more women than men (Khanna, 2019). Although, it is a common perception however few surveys claimed a lower rate of men detailed IPSB, and in particular mild IPSB (Holland et al., 2016). The findings’ discernment may stem from the truth that patients facing a neurological deficit may show an unmistakable cause for IPSB, such as medicines directed influence behaviour or a patient’s battle with his or her sexuality (Moore and Mennicke, 2020). On the other hand, it was reported that the most elevated extent of respondents has experienced IPSB on an orthopaedics revolution concerning the closeness of predominance over intense care, rehabilitation, and domestic care settings that not ought to be cantered on a given zone (Lin et al., 2020).

The authors have clarified that understudies tend to disregard IPSB may be utilizing hush to viably dispose of the issue or utilizing it as a cover methodology that may contribute to its recurrence. In addition to it, Brooks and Perot demonstrated that the presence of sexual badgering may stem from a misguided judgment. Moreover, these misinterpretations may energize a continuation of badgering therefore foremost viable procedure should be planned against the harasser. A study demonstrated that many therapists reported discussing the behaviour with the patient although we must learn to recognize what is happening within the communication framework and have strategies accessible when challenges with intuition emerge (Thakur and Paul, 2017).

Strength

To the best of author’s knowledge, this study is the first to be conducted in Pakistan to rule out the inappropriate sexual behaviors of patient towards therapists. The study has highlighted the profound percentages in some questions that need to be evaluated in future studies.

Limitations

Several limitations have occurred in this study including comparatively small sample and number of unanswered question by the participants that may have led to bias results. Although the response rate has demonstrated low percentage of IPSB, yet the factors and gender-wise percentage were not estimated. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized and require comprehensive evaluations in future.

Future Directions

Future studies are recommended to evaluate the IPSB in different settings, considering diverse work fields and gender-wise aspect to rule out the origin of issue. Moreover, therapists training and sound knowledge should be promoted for the prevention of such problem.

Conclusion

It was concluded that IPSB is indeed present in healthcare workers; however, the percentage is comparatively low. However, few has expressed their disgust and raised voice to report the issues. Therefore, future studies should be conducted considering therapists training and awareness to identify such perpetrators in their setting and inform the management to take important steps to address it.

References

- Abdullah NC, Rosnan H, Yusof N. Sexual Harassment in Healthcare SMEs: Behaviours of medical practitioners and medical tourists. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal. 2018 Aug 1;3(8):65-71.

- Aman T, Asif S, Qazi A, Aziz S. Perception of sexual harassment at workplace, knowledge of working women towards workplace harassment act 2010. Khyber Journal of Medical Sciences (KJMS). 2016 May;9(2):230-6.

- Aycock LM, Hazari Z, Brewe E, Clancy KB, Hodapp T, Goertzen RM. Sexual harassment reported by undergraduate female physicists. Physical Review Physics Education Research. 2019 Apr 22;15(1):010121.

- Burke Draucker C. Responses of nurses and other healthcare workers to sexual harassment in the workplace.

- Cambier Z, Boissonnault JS, Hetzel SJ, Plack MM. Physical therapist, physical therapist assistant, and student response to inappropriate patient sexual behavior: results of a national survey. Physical therapy. 2018 Sep 1;98(9):804-14.

- Campbell M. Disabilities and sexual expression: A review of the literature. Sociology Compass. 2017 Sep;11(9):e12508.

- Crowley BZ, Cornell D. Associations of bullying and sexual harassment with student well-being indicators. Psychology of violence. 2020 Aug 6.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Training programs and reporting systems won’t end sexual harassment. Promoting more women will. Harvard Business Review. 2017 Nov 15;70(4):687-702.

- Fitzgerald LF, Cortina LM. Sexual harassment in work organizations: A view from the 21st century.

- Gruber J, Fineran S. Sexual harassment, bullying, and school outcomes for high school girls and boys. Violence against women. 2016 Jan;22(1):112-33.

- Hadjicharalambous I, Sisco M. Verbal Sexual Coercion among a US College Sample: Patterns of sexual boundary violations and predictive factors. Journal of European Psychology Students. 2016 Apr 26;7(1).

- Holland KJ, Rabelo VC, Gustafson AM, Seabrook RC, Cortina LM. Sexual harassment against men: Examining the roles of feminist activism, sexuality, and organizational context. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2016 Jan;17(1):17.

- Ilik F, Büyükgöl H, Kayhan F, Ertem DH, Ekiz T. Effects of inappropriate sexual behaviors and neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients with Alzheimer disease and caregivers’ depression on caregiver burden. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology. 2020 Sep;33(5):243-9.

- Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. Jama. 2016 May 17;315(19):2120-1.

- Kabat-Farr D, Crumley ET. Sexual harassment in healthcare: a psychological perspective. Online J Issues Nurs. 2019 Jan 1;24(1):1-2.

- Kahsay WG, Negarandeh R, Nayeri ND, Hasanpour M. Sexual harassment against female nurses: a systematic review. BMC nursing. 2020 Dec;19(1):1-2.

- Khanna A. Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace.

- Lin JS, Lattanza LL, Weber KL, Balch Samora J. Improving sexual, racial, and ethnic diversity in orthopedics: an imperative. Orthopedics. 2020 May 1;43(3):e134-40.

- Lockwood W. Sexual harassment in healthcare.

- Moore J, Mennicke A. Empathy deficits and perceived permissive environments: sexual harassment perpetration on college campuses. Journal of sexual aggression. 2020 Sep 1;26(3):372-84.

- Perera S, Abeysinghe S. Combatting Workplace Sexual Harassment of Female Employees in Sri Lanka: An Empirical A nalysis. InProceedings of APIIT Business, Law & Technology Conference, 201 7 2017.

- Rowe M, Macauley M. Giving voice to the victims of sexual assault: the role of police leadership in organisational change. Policing: an international journal. 2019 Jun 10.

- Strauss S. Overview and summary: sexual harassment in healthcare. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2019;24(1):10-3912.

- Thakur MB, Paul P. Sexual harassment in academic institutions: A conceptual review. Journal of Psychosocial Research. 2017;12(1):33.

- Viglianti EM, Oliverio AL, Meeks LM. Sexual harassment and abuse: when the patient is the perpetrator. The Lancet. 2018 Aug 4;392(10145):368-70.

- Vrees RA. Evaluation and management of female victims of sexual assault. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2017 Jan 1;72(1):39-53.

- Zeiger MF. Beyond Consolation. Cornell University Press; 2018 May 31.

The Ziauddin University is on the list of I4OA (https://i4oa.org/) & I4OC (https://i4oc.org/).

![]() This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Conflict of Interest: The author (s) have no conflict.

[i] Senior lecturer Occupational Therapist at Sindh Institute Of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4638-1756