ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Parents with Down syndrome children may be unfamiliar with coping strategies because of limited knowledge, negative attitude and inappropriate practice. To the best of author’s knowledge, no study has been conducted in Pakistan till date to explore the issue.

METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among parents of children with Down syndrome, enrolled in the study via convenience sampling technique. Data was collected on self-administered questionnaire based on parental knowledge, attitude and practice on Down syndrome distributed via email or WhatsApp group.

RESULTS

A total number of 24 parents with Down syndrome included in this study involving majority of mothers (52.2%) showed that (79.2%) parents understand that Down syndrome is a genetic disorder, (91.7%) agreed that children are born through it. Moreover, (83.3%) think that the syndrome can be detected during pregnancy through prenatal tests whereas (100%) showed that physiotherapy, occupational and speech therapy plays a pivotal role in the management of disorder. Besides, (83.3%) parents have recommended the special health services. Therefore, (87.5%) parents will prefer to seek the genetic counselling when planning for next child.

CONCLUSION

It was concluded that majority of parents have demonstrated the sound knowledge, positive attitude and proactive practice among parents with Down syndrome children. Thus, multicenter large scale studies should be conducted to investigate the factors associated to parent-child relationship and promote education for better health outcomes.

KEYWORDS

Down syndrome, disability, intellectual, ADLs, Knowledge, Management.

Hira Masood

Bakhtawar Amin Hospital

Head of Department

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-1858-5751

Dr. Fathima Zeenath Nasurdeen

Department of Ayurveda, Ministry of Indigenous Medicine, Sri Lanka

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-4660-6780

Dr. Anavarathan Vallipuram

Senior Lecturer,

Faculty of Applied Science, Trincomalee Campus, Eastern University Sri Lanka

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5987-2757

[Masood H, Nasurdeen FZ, Vallipuram A. A Cross-Sectional Survey on Knowledge, Attitude and Practice in Parents with Down syndrome Children

Pak.j.rehabil. 2022; 11(1):27-36]

DOI: 10.36283/pjr.zu.11.1/005

INTRODUCTION

Down syndrome (DS) is characterized by a chromosomal disorder that has a common occurrence among children i.e. in about 1 in every 700 babies1. It is the most prevalent chromosomal defect, estimated to be 1 in 691 live births in the United States1,2. Despite, in Pakistan, its overall incidence has been reported as 1/700 live births.

The condition is associated with mental retardation which not only affects the well-being of affected individuals but also their families2. Furthermore, it is indicated that DS occurrence increase with the progressing age of the pregnant mother3. Moreover, physical features and behaviors are similar in this due to the chromosomal characteristics i.e. Trisomy 21 occurs when an extra part of a whole chromosome is translocated to a dissimilar chromosome4. According to the ICF Model (International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health), individuals with DS have poor physical health, low cardiovascular fitness, autoimmune and metabolic problems5. Moreover, mental health is also predominantly affected due to comorbid autism. Therefore, these impairments lead to activity limitations and participation restrictions thereby endanger the quality of life6. A number of studies advocated that understanding DS individuals may develop strengths and challenges amongst them that are important to maximize their participation in society. Moreover, certain educational programs constitutes of simulated, cognitive, or educational training that may also serve as a key factor for the effective management of the condition. However, it is crucial that the primary caregivers must have sound knowledge for the understanding of their child in special need7. A number of healthcare practitioners indicated the direction to support parent involvement to improve their child’s ability. For this reason, the attitude of parents is directionally proportionate to the child’s improvement8. However, due to the overburden of disability sometimes parents showed stress, mood swings, or other characteristics9. A socially preintegrated rejection of DS is shown in the termination of a pregnancy due to prenatally diagnosed DS8-9. This runs counter to current ideas of tolerance and anti-discrimination, particularly in cultures where these principles coexist with the legalisation of elective abortion. The possibility of preventing the “person” from being a part of one’s life is available with antenatal diagnosis. As members of society, parents’ fears about having a child with DS are heavily influenced by unfavorable socially shared information and attitudes about adopting a child with special needs and stigmatizing physical characteristics10. Therefore, parent knowledge is substantial for the child’s improvement and disability management. It is evident that raising a child with a special need is a challenge for the caregivers to achieve work-life balance therefore mediated interventions is required to improve the communication between them10,11. Furthermore, a number of factors involving parental behavior, level of satisfaction, and means of communication may also be addressed to promote better health outcomes11. The real-life experience of parents who have children with DS, on the other hand, is unexpectedly more upbeat, since the majority of these parents state that their children with DS are a source of love, pride, and pleasure for them as 99% of the 2,044 parents said they love their son or daughter, 97% said they were proud of them, and 79% said they had a more optimistic attitude on life as a result of them10-12. Parents also claimed that 95% of their sons or daughters without DS get along well with their DS siblings. This refers to the families’ adaptation to their children’s chronic illnesses and the maturing of their perspectives of what living with such a child entails13. Similarly, virtually all persons with DS report having pleasant lives and satisfying familial and friendly interactions, and they welcome healthcare experts to help them enhance their social image10,14. Despite the fact that DS has been studied for almost a century, there are still significant gaps in our knowledge. The impact of children with DS on their families is a persistent issue. A “Down syndrome advantage,” according to some researchers, is the belief that parents and families of children cope better than parents and families of children with other disabilities due to particular kid traits15. However, the existence of such an advantage has long been questioned, and parental age, education, and socioeconomic position may all be other-than-child elements that contribute to these families’ well-being16. Many studies have found that parents with disabled children encounter a variety of challenges in caring for them. The demands of Down syndrome children in maturity, on the other hand, are still unknown. Parents of children DS have also claimed that the disorder may endure into adulthood, with varying social, emotional, and personal demands17,20. Parents of children diagnosed with autism or DS adapt variety of coping strategies to cope with the devastating news21,22. Coping refers to the cognitive and behavioral attempts undertaken to cope with and lessen the stress brought on by various problems23. Many studies indicated that parents often face several barriers in taking care of their children with disabilities12. However, the needs of DS children in adulthood are still unclear. Furthermore, it was advocated by the parents of Down syndrome that disorder may persist in adulthood with varying social, emotional, and personal needs13,14. Another study described that health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with Down syndrome have poorer physical well-being, social support and peer dimension that may be source of great distress among parents and the children15. Furthermore, psychosocial screening may also be a valuable addition for routine clinical practice. Despite being a primary caregiver, mothers do not often report everyday problems while fathers tend to have more difficulties than across most domains frequently16. Therefore, work-life based balance interventions should be implemented for beneficial outcomes and to promote effective healthcare outcomes. Furthermore, the desired attitude is also required to control the child’s involvement in a number of circumstances for better management, although several parents might have changed in their attitudes due to the overburden of disability care that causes them to lose interest in child activities17-20. Besides, the majorities of parents tend to be unaware of their children’s condition and do not possess any information about the possible etiological factors18. Therefore, it is very important for the family and community to induct an early interference for individuals with Down syndrome for better health-related outcomes. Moreover, educational materials, as well as misconceptions, should be addressed and corrected in order to benefit the families of the affected children. However, there is insufficient evidence to determine parent-mediated interventions for improving the communication outcomes in children with DS22,24. Therefore, multicenter trials should be conducted to highlight the need for the development of certain frameworks to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions.

METHODOLOGY

Study Setting: Data was collected from Karachi Down Syndrome Program (KDSP) and Pakistan Centre of Autism.

Target Population: Guardian/Parents of DS children.

Study Design: Cross-sectional survey.

Duration of Study: 6-8 months.

Sampling Technique: Non-Probability Convenience Sampling Technique.

Sample Size: n=150

Sample Selection

Inclusion criteria

- Guardian/parents of DS children enrolled in rehabilitation program for ≥6 months.

Exclusion criteria

- Refusal of participation or incomplete filled questionnaire.

Data Collection Tool:

The questionnaire is self-administered comprised of 5 questions based on Knowledge, 6 on Attitude and 10 on practice. The responses were analyzed on these three aspects by participants.

Data Collection Procedure: The participants were enrolled in study through convenience sampling technique from primary and tertiary care hospitals. The questionnaire was formulated in Google Docs and sent to participants via email or Whatsapp group. Prior to collection, all participants were given consent form to ensure their voluntary participation. After their consent, understanding about the questionnaire was ensured in order to record the responses on the self-administered questionnaire. The data was analyzed upon completion of sample.

Data Analysis Strategy: Data was analyzed on Google Docs Editor. The demographic characteristics of the participants were represented through frequency, mean and standard deviations whereas the participant responses were evaluated through frequency and percentage.

Ethical Considerations: Ethical consideration was taken via verbal and written consent by the participant before starting the data collection. All information of the participants was kept anonymous under investigator’s supervision.

RESULTS

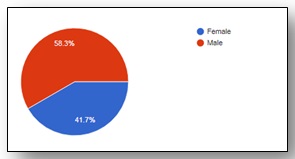

A total number of 24 parents with DS included in this study with 14 (58.3%) males and 10 (41.7%) females involved majority of mothers (52.2%) working as a housewife (20.8%), having age of 40 years (12.5%). The gender-wise distribution of participants is illustrated as Figure-1.

Figure-1 shows gender-wise distribution of participants

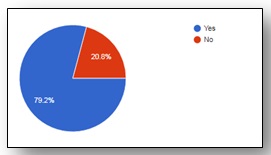

It was showed that (79.2%) parents understand that DS is a genetic disorder as shown in Figure-2, while (91.7%) agreed that children are born through it, otherwise (95.8%) believed the absence of disorder in their siblings. Moreover, (83.3%) think that the syndrome can be detected during pregnancy through prenatal tests.

Figure-2 shows understanding of participants regarding Down syndrome

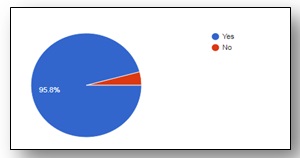

It was further responded that (87.5%) parents were disagreed that disorder go away as the child with DS grows and (75%) answered that the disorder cannot be cured or (70.8%) prevented whereas (100%) showed that physiotherapy, occupational and speech therapy plays a pivotal role in the management of disorder. The parents also feels that the child needs more care than their other children (91.7%); however (70.8%) reported to feel stressed between the caring of child and meet responsibilities as shown in Figure-3. Such that they would prefer to go outside at party or picnic without their child (79.2%) and feel uncomfortable with his/her in public places (29.2%) respectively.

Figure-3 shows participants responses on caring of child and meet responsibilities

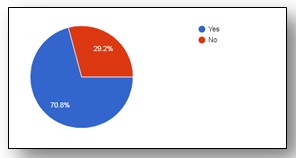

It was further showed that (83.3%) parents has recommended the special health services as (95.8%) think that playing parental role improved the life of DS children while (95.8%) supports their children in living a normal life as shown in Figure-4. On the other hand, (83.3%) parents have discussed the impact of DS and (83.3%) its possible complications. Moreover, (87.5%) agreed to enrol their child in rehab at an earliest for the management of associated complications. Further, (91.7%) parents revealed that they have been practice home based exercise with their child but (54.2%) face difficulty in while providing it, although (95.85%) followed the therapist’s instruction. Therefore, (87.5%) parents will prefer to seek the genetic counselling when planning for next child. Consequently, all of them think that the parenting of DS is indeed challenging regardless of child ability therefore they prefer to attend number of awareness programs to improve their child contribution in society.

Figure-4 shows participants responses on supporting their children living a normal life

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study showed that (79.2%) parents understand that DS is a genetic disorder, (91.7%) agreed that children are born through it. Moreover, (83.3%) think that the syndrome can be detected during pregnancy through prenatal tests. It was further answered (75%) that the disorder cannot be cured whereas (100%) showed that physiotherapy, occupational and speech therapy plays a pivotal role in the management of disorder. Besides, (83.3%) parents has recommended the special health services as (95.8%) think that playing parental role improved the life of DS children while (95.8%) supports their children in living a normal life. Therefore, (87.5%) parents will prefer to seek the genetic counselling when planning for next child. Consequently, all of them think that the parenting of DS is indeed challenging regardless of child ability therefore they prefer to attend number of awareness programs to improve their child contribution in society. Thus, this study demonstrated the sound knowledge, positive attitude and proactive practice among parents with Down syndrome children.

Education about Down syndrome may also aid in the reduction of societal barriers such as the integration of people with DS into everyday settings such as school and the workplace24,26. A number of studies found that women have some knowledge about DS but tend to have many misconceptions about the condition18. Therefore, it is suggested that primary caregivers, in particular women should be given sound information about clinical perspectives of the syndrome. Moreover, culturally diverse educational materials about Down syndrome are also recommended to be devised through the channels of healthcare professionals19. It’s possible that the increased presence of people with DS in schools and communities in recent years has resulted in a better understanding of developmental milestones and more optimistic expectations for adult accomplishments24. As limited studies have been conducted to explore KAP in DS children parents, despite few studies in association with it Gilmore et al19 found that majority of individuals working as teachers or community member knew that DS is a genetic disorder while knowledge related to its medical complications were found to be scarce. In addition, Moyer et al20 revealed that primary caregivers of DS, in particular mothers are unaware of the physical challenges experienced by their children thereby uncertain of the future consequences. Furthermore, quite a few data are available on the region-wise prevalence of DS therefore epidemiologists must take relevant steps to include data on birth prevalence with respect to age and ethnicity. Consequently, Phillips et al21 showed the persistent delusions about DS that may lead to low demands and expectations from them thus impede development and social integration. For that reason, educational elements must be appropriately designed to address these misconceptions to better prepare and benefit families who have a child with DS24-26. Integrating children with DS into regular schools is a highly beneficial method because it improves their speech and cognitive skills24, engages them in regular activity19, and improves their sociability. Children with Down syndrome who grow up in regular social settings are more likely to form friendships than those who grow up in specialized facilities or group homes26,28. Thus, our results offer insights into how educators might tailor information about it to meet the requirements of families, providing relevant information related to its management so that primary caregivers shall be able to apply it in everyday activities. Expectant parents appear to be lacking in critical information for making decisions therefore they should be provided enough information to make an educated decision before being screened for congenital abnormalities, according to the Council of Europe 22.

STRENGTH

To the best of author’s knowledge, this study is the first to be conducted in Pakistan to explore the knowledge, attitude and practice of parents with DS children. Due to socio-cultural barriers, the concept is reluctant to be explored at full-potential; despite of the rising interventions, parental-attitude and knowledge based studies are limited.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There are several limitations faced in the study including relatively small sample size due to ongoing pandemic situation, thus less number of parents with DS were approached. Moreover, lack of standardized use of questionnaire may lead to bias parental opinions, besides; questionnaire didn’t consist of biased options that might be helpful to evaluate the responses on varying basis. Thus, multicenter large scale studies should be conducted to investigate the factors associated to parent-child relationship and promote education for better health outcomes.

CONCLUSION

It was concluded that majority of parents have demonstrated the sound knowledge, positive attitude and proactive practice among parents with Down syndrome children. Thus, multicenter large scale studies should be conducted to investigate the factors associated to parent-child relationship and promote education for better health outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Shin M, Besser LM, Kucik JE, Lu C, Siffel C, Correa A. Prevalence of Down syndrome among children and adolescents in 10 regions of the United States. Pediatrics. 2009 Dec 1;124(6):1565-71.

- Bryant LD, Ahmed S, Ahmed M, Jafri H, Raashid Y. ‘All is done by Allah’. Understandings of Down syndrome and prenatal testing in Pakistan. Social science & medicine. 2011 Apr 1;72(8):1393-9.

- Martin GE, Klusek J, Estigarribia B, Roberts JE. Language characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome. Topics in language disorders. 2009 Apr;29(2):112.

- Taub JW, Ge Y. Down syndrome, drug metabolism and chromosome 21. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2005 Jan;44(1):33-9.

- Anil MA, Shabnam S, Narayanan S. Feeding and swallowing difficulties in children with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2019 Aug;63(8):992-1014.

- Meyer C, Theodoros D, Hickson L. Management of swallowing and communication difficulties in Down syndrome: A survey of speech-language pathologists. International journal of speech-language pathology. 2017 Jan 2;19(1):87-98.

- Masgutova S, Akhmatova N, Ludwika S. Reflex profile of children with down syndrome improvement of neurosensorimotor development using the MNRI® reflex integration program. International Journal of Neurorehabilitation 2016;3(197):2376-0281.

- Labby A, Mace JC, Buncke M, MacArthur CJ. Quality of life improvement after pressure equalization tube placement in Down syndrome: a prospective study. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Sep 1;88:168-72.

- Starmer AJ, Frintner MP, Matos K, Somberg C, Freed G, Byrne BJ. Gender discrepancies related to pediatrician work-life balance and household responsibilities. Pediatrics. 2019 Oct 1;144(4):e20182926.

- Horne RS, Sakthiakumaran A, Bassam A, Thacker J, Walter LM, Davey MJ, Nixon GM. Children with Down syndrome and sleep disordered breathing have altered cardiovascular control. Pediatric Research. 2020 Nov 23:1-7.

- Lee CE, Burke MM, Arnold CK, Owen A. Comparing differences in support needs as perceived by parents of adult offspring with down syndrome, autism spectrum disorder and cerebral palsy. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2019 Jan;32(1):194-205.

- Krueger K, Cless JD, Dyster M, Reves M, Steele R, Nelson Goff BS. Understanding the systems, contexts, behaviors, and strategies of parents advocating for their children with Down syndrome. Intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2019 Apr;57(2):146-57.

- Lyons R, Brennan S, Carroll C. Exploring parental perspectives of participation in children with Down Syndrome. Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 2016 Feb;32(1):79-93.

- Patton S, Hutton E. Parents’ perspectives on a collaborative approach to the application of the Handwriting Without Tears® programme with children with Down Syndrome. Australian occupational therapy journal. 2016 Aug;63(4):266-76.

- Al-Mosawi AJ. The etiology of mental retardation in Iraqi children. autism. 2019;1:4-7.

- Gilson KM, Davis E, Corr L, Stevenson S, Williams K, Reddihough D, Herrman H, Fisher J, Waters E. Enhancing support for the mental wellbeing of parents of children with a disability: developing a resource based on the perspectives of parents and professionals. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2018 Oct 2;43(4):463-72.

- Padilla-Petry P, Saladrigas-Tuà M. Autism in Spain: parents between the medical model and social misunderstanding. Disability & Society. 2020 Sep 30:1-22.

- Akbar S, Woods K. The experiences of minority ethnic heritage parents having a child with SEND: a systematic literature review. British Journal of Special Education. 2019 Sep;46(3):292-316.

- Gilmore L, Cuskelly M. Associations of child and adolescent mastery motivation and self-regulation with adult outcomes: a longitudinal study of individuals with Down syndrome. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2017 May 1;122(3):235-46.

- Moyer A, Salovey P, Casey-Cannon S. Challenges facing female doctoral students and recent graduates. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999 Sep;23(3):607-30.

- Phillips BA, Conners F, Curtner-Smith ME. Parenting children with down syndrome: An analysis of parenting styles, parenting dimensions, and parental stress. Research in developmental disabilities. 2017 Sep 1;68:9-1.

- Europe C. Recommendation No. R (90) 13 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on Prenatal Genetic Screening, Prenatal Genetic Diagnosis and Associated Genetic Counselling. International digest of health legislation. 1990;41(4):615-24.

- Folkman S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysis. Kango kenkyu. The Japanese journal of nursing research. 1988;21(3):243-60.

- Gilmore L, Campbell J, Cuskelly M. Developmental expectations, personality stereotypes, and attitudes towards inclusive education: Community and teacher views of Down syndrome. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2003 Mar 1;50(1):65-76.

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, Anderson P, Mason CA, Collins JS, Kirby RS, Correa A. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2010 Dec;88(12):1008-16.

- Antonak R, Livneh H. Measurement of attitudes towards persons with disabilities. Disability and rehabilitation. 2000 Jan 1;22(5):211-24.

- Urbano RC, Hodapp RM. Divorce in families of children with Down syndrome: A population-based study. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007 Jul;112(4):261-74.

- Cahill BM, Glidden LM. Influence of child diagnosis on family and parental functioning: Down syndrome versus other. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1996;101(2):149-60.